Democracy or Dictatorship

The concept of leadership in a democracy can be highly problematic.1 Benjamin Barber (2004), a prominent researcher of democracy and democratic institutions, writes that, “A leader strong enough to do everything we would like done for us is strong enough to deprive us of the capacity to do anything at all for ourselves.”2 Ruscio (2004), writing in The Leadership Dilemma in Modern Democracy, also captures the prevailing skepticism well:

“Suspicion of rulers, concern over their propensity to abuse power in their own self-interest, the need to hold them accountable, and the belief that legitimate power is lodged originally in the people and granted to leaders only with severe contingencies, all are fixed stars in the democratic galaxy. In many respects, democracy came about as the remedy to the problem of leadership, at least as defined by a long list of political philosophers. Fear of leadership is a basic justification for democratic forms of government.”3

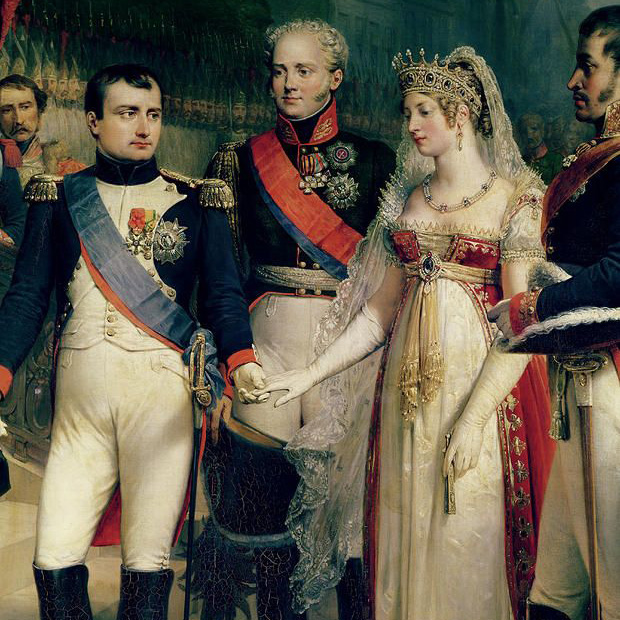

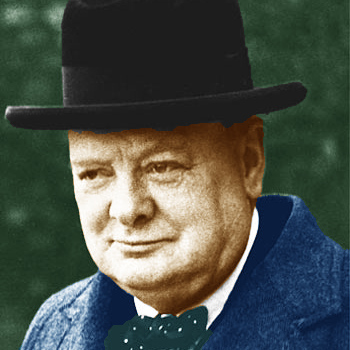

Perhaps this fear is even more intense in the presence of the wildly popular and powerful charismatic leader. No doubt, the presidency of Donald Trump and the charismatic bond he has with his followers has added to the fears many hold regarding the precariousness and fragility of democracy. Fond of quoting the Mexican revolutionary leader Zapata who said, “strong leaders make a weak people;”4 Barber, is notoriously uncomfortable with leadership in a democracy.5 Barber (2003) writes: “The statesmanship of a leader such as Churchill may stultify the liberty of an admiring but passive followership no less than might the charisma of a Hitler.”6

Similarly, Gary Wills, the renowned Kennedy biographer, in his study of charismatic political leadership and American democracy writes: “we do the most damage under the Presidents we love most.”7

Arthur Schlesinger, a former adviser to President Kennedy also had a healthy skepticism of charismatic leadership in democracy. Schiffer (1973) writes:

“Schlesinger, quite articulate in this direction, has argued that in modern society there exists a practical dominance of forces, personality appeals, and policies that leaves no room whatever for charisma, because charisma is basically incapable of dealing with the realities of a democratic culture.”8

So, then, does charismatic leadership have a place in democracy? The question, though openly debated, has been far from sufficiently addressed. Nonetheless, support, however tempered, clearly exists. Even Schlesinger, paradoxically, who leaves “no room” for charisma, thought there might be a role for the charismatic leader in times of crisis.9 Moreover, there are a number of arguments put forth (including by Max Weber himself) which undeniably suggest that charismatic leadership has a critically important role in democracy.

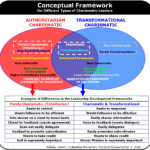

The Two Faces of Charisma

On the question of charismatic leadership in a democracy, though many of the leading thinkers seem to come down more definitively on one side or the other, there are at least a few (myself included) who are quick to say that it very much depends on the type of charismatic leadership (an important part of the research problem this study seeks to address) or, even more to the point, that it is a matter of degree.

University of California Professor, Elizabeth Zechmeister (2006) weighs in: “Charismatic leadership in itself is not at all antithetical to democracy. However, in its extreme form, which is usually in times of crisis, and coupled with a leader who inherently has instinctive charismatic tendencies, it certainly can be somewhat dangerous.”10

Perhaps the “it depends” argument for charismatic leadership in democracy is most vivid by juxtaposing the impact that different highly charismatic leaders have had on their own governments. Here we can call to mind the different consequences of Franklin Roosevelt and Adolf Hitler or John Kennedy and Joseph Stalin. If there is merit to the psychoanalytic interpretation of charismatic leadership and the followers of charismatics are “neutral as to the content of the leader’s message or vision”11 (no matter how dastardly), then this would certainly seem to intensify the importance of further study and the potential threat that charismatic leadership may pose to an open and democratic society.

It seems, in regards to charismatic political leadership, that a healthy skepticism, a heightened awareness, and a robust understanding of the different types as well as the responsibilities of followers and of citizenship are all essential to the preservation of a free and open society.

As Arthur Schlesinger writes:

“An adequate democratic theory must recognize that democracy is not self-executing; that leadership is not the enemy of self-government but the means of making it work; that followers have their own stern obligation, which is to keep leaders within rigorous constitutional bounds; and that Caesarism is more often produced by the failure of feeble governments than by the success of energetic ones.”12

,

,

after executing a successful military coup d’état. With estimates ranging between 100,000 and 500,000 deaths as the result of his despotic rule, Idi Amin is considered one of the most brutal despots in history. A boxing champion who served in the British Army, the extremely charismatic and flamboyant Idi Amin began his rule with a number of popular actions, but he was a brutal, bloodthirsty tyrant who butchered his opponents and was completely incompetent in regards to effectively ruling a nation state. Typical of dictators and tyrants, Idi Amin was extremely paranoid and reportedly fed several of his own ministers to crocodiles.

after executing a successful military coup d’état. With estimates ranging between 100,000 and 500,000 deaths as the result of his despotic rule, Idi Amin is considered one of the most brutal despots in history. A boxing champion who served in the British Army, the extremely charismatic and flamboyant Idi Amin began his rule with a number of popular actions, but he was a brutal, bloodthirsty tyrant who butchered his opponents and was completely incompetent in regards to effectively ruling a nation state. Typical of dictators and tyrants, Idi Amin was extremely paranoid and reportedly fed several of his own ministers to crocodiles.